December 13, 2010

I am in Ranong and cannot sleep. For the geographically challenged, think Isthmus of Kra in southern Thailand at the point where Burma ends and Muslim Thailand begins, going down to Malaysia. I am in the Marist Fathers' house.

I am in Ranong and cannot sleep. For the geographically challenged, think Isthmus of Kra in southern Thailand at the point where Burma ends and Muslim Thailand begins, going down to Malaysia. I am in the Marist Fathers' house.

Outside, the fish factory that never sleeps is churning out packaged prawns for markets far away. The people working in it are illegal migrants from Burma, paid a pittance and treated as sub humans. As illegals, they can be arrested by the Thai police but usually pay a 'fine' to escape jail — for a while.

Young Burmese men as young as 15 and 16 come off the fishing boats owned by Thai or Burmese entrepreneurs, their pockets brimming with baht, swagger in their step, and head for the tiny brothels by the side of the road near the port, where HIV awaits them.

Only the strong return from the fishing trips. If you are ill and cannot work, you can be tipped into the sea along with the other rubbish for the seagulls. If you trip and fall overboard, the boat ploughs on regardless.

Young Burmese women in longyi, with long, black hair tied in a ponytail, stand out and can be abducted by men in dark glasses in passing cars and taken to the brothels and bars of Phuket, Bangkok or Pattaya. Being illegal with no papers or rights, they disappear, to the despair of their parents. It's part of the dangerous deal of crossing the border from a regime that regards most of its people as scum to a country where a subsistence income can at least be earned.

HIV is rife here — among the Thai and the Burmese. The Global Fund gives money to Thailand for those living with the virus but Thai doctors in Ranong, which has more Burmese than Thai, say the cash for anti-retrovirals is only for Thais. So the Burmese die. A few are saved by the Marists among other religious groups with funds from an NGO. But who decides who lives and who dies?

A young Burmese boy of nine who was found abandoned in the forest and then cared for by a poor Burmese family with support from the Marists plays with the priest's big toe. He ran away again but promised he wouldn't do it in future if 'Father' bought him a TV. He is not quite ready for the factory or the fishing boats and is desperately vulnerable.

A young girl of 15 dressed in a school uniform, her hair cut short like a Thai to escape abduction, is too young for the ACU online diploma but asks to attend anyway to learn, just to be part of the dream of having higher education. She is lucky that her parents don't force her into the fish factory.

We visit a young fishermen and his wife in a wooden warren of tiny hovels for the dispossessed. It leans over the water so that when the Thai police come they can abandon their few possessions (an ancient black and white TV, a few dishes, a mattress) and dive into the river to escape the fine/bribe.

Both have HIV and they lost their baby to the virus the year before. They show us a grainy picture of the child, beautiful as all infants are, and we are stunned into silence. The dignity of the couple in their immense human suffering awes us.

A few hours south of here, tourists soak up the sun on the beaches of Ko Samui, Phuket and the islands of the film, The Beach. In the lead-up to Christmas, the contrast is striking.

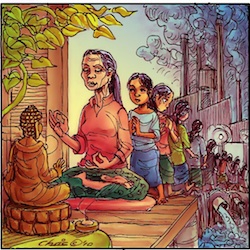

In Ranong, through an open door, I see a Burmese woman in the lotus position meditating and venerating the Buddha, hoping the next incarnation will be better than the misery of this existence, as a beatific smile crosses her face.

Happy Christmas.

I am in Ranong and cannot sleep. For the geographically challenged, think Isthmus of Kra in southern Thailand at the point where Burma ends and Muslim Thailand begins, going down to Malaysia. I am in the Marist Fathers' house.

I am in Ranong and cannot sleep. For the geographically challenged, think Isthmus of Kra in southern Thailand at the point where Burma ends and Muslim Thailand begins, going down to Malaysia. I am in the Marist Fathers' house.Outside, the fish factory that never sleeps is churning out packaged prawns for markets far away. The people working in it are illegal migrants from Burma, paid a pittance and treated as sub humans. As illegals, they can be arrested by the Thai police but usually pay a 'fine' to escape jail — for a while.

Young Burmese men as young as 15 and 16 come off the fishing boats owned by Thai or Burmese entrepreneurs, their pockets brimming with baht, swagger in their step, and head for the tiny brothels by the side of the road near the port, where HIV awaits them.

Only the strong return from the fishing trips. If you are ill and cannot work, you can be tipped into the sea along with the other rubbish for the seagulls. If you trip and fall overboard, the boat ploughs on regardless.

Young Burmese women in longyi, with long, black hair tied in a ponytail, stand out and can be abducted by men in dark glasses in passing cars and taken to the brothels and bars of Phuket, Bangkok or Pattaya. Being illegal with no papers or rights, they disappear, to the despair of their parents. It's part of the dangerous deal of crossing the border from a regime that regards most of its people as scum to a country where a subsistence income can at least be earned.

HIV is rife here — among the Thai and the Burmese. The Global Fund gives money to Thailand for those living with the virus but Thai doctors in Ranong, which has more Burmese than Thai, say the cash for anti-retrovirals is only for Thais. So the Burmese die. A few are saved by the Marists among other religious groups with funds from an NGO. But who decides who lives and who dies?

A young Burmese boy of nine who was found abandoned in the forest and then cared for by a poor Burmese family with support from the Marists plays with the priest's big toe. He ran away again but promised he wouldn't do it in future if 'Father' bought him a TV. He is not quite ready for the factory or the fishing boats and is desperately vulnerable.

A young girl of 15 dressed in a school uniform, her hair cut short like a Thai to escape abduction, is too young for the ACU online diploma but asks to attend anyway to learn, just to be part of the dream of having higher education. She is lucky that her parents don't force her into the fish factory.

We visit a young fishermen and his wife in a wooden warren of tiny hovels for the dispossessed. It leans over the water so that when the Thai police come they can abandon their few possessions (an ancient black and white TV, a few dishes, a mattress) and dive into the river to escape the fine/bribe.

Both have HIV and they lost their baby to the virus the year before. They show us a grainy picture of the child, beautiful as all infants are, and we are stunned into silence. The dignity of the couple in their immense human suffering awes us.

A few hours south of here, tourists soak up the sun on the beaches of Ko Samui, Phuket and the islands of the film, The Beach. In the lead-up to Christmas, the contrast is striking.

In Ranong, through an open door, I see a Burmese woman in the lotus position meditating and venerating the Buddha, hoping the next incarnation will be better than the misery of this existence, as a beatific smile crosses her face.

Happy Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment